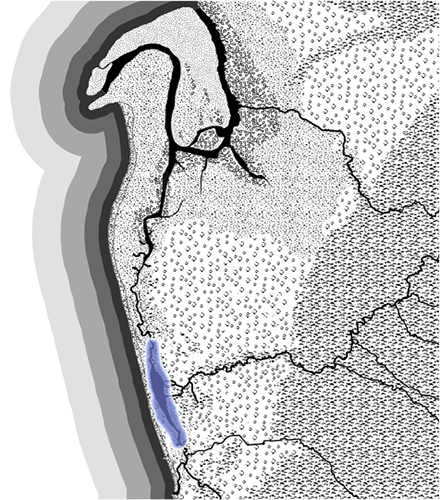

Witongga tarto low swampy reed country was an ephemeral wetland system stretching from Pathawilyangga (Patawalonga/Glenelg) to Yerta Bulti (Port River/Estuary). Lying between the coastal dunes and a system of red sand dunes to the east, Witongga was fed by the waters of Karrawirrparri and filtered them as they slowly drained to the sea.

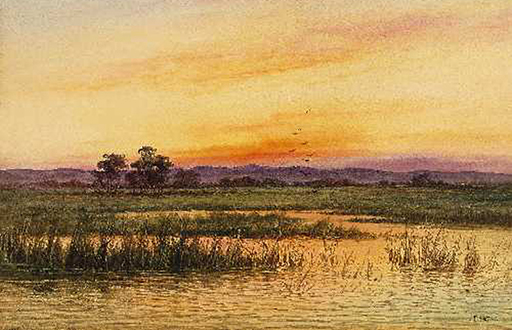

(Extract from) Reedbeds, James Ashton, c.1890 (White Collection)

Witongga was a prime summer living area for Kaurna meyunna as it was rich in plant and animal life. There were plenty of yabbies, mussels, waterfowl and small animals and snakes to eat. Another food source was tadpoles as recollected by Edwin Mitchell Smith (later Surveyor-General) who arrived in the colony as a small child in 1850:

When we reached Australia, we lived … near Captain Sturt’s house at the Grange. I know the exact spot now. I don’t remember going there but my recollection of a lot of blacks being there is very vivid. These people caught a lot of tadpoles in the creek, made a fire, placed stones in it until they were quite hot and then laid rushes on these and placed the tadpoles thereon until they were cooked. These embryonic frogs were evidently a great dainty, as was also snake, which they cooked (Smith, 1920).

Witongga provided many useful plants and trees; wito reed, bulrushes, karra river red gum, karko sheoak, teatree and wattles. The reeds were used for weaving baskets, nets and string as well as kootpi reed spears.

Cootpe-a reed spear, W. A. Cawthorne, 1855 (Mitchell Library)

An Aboriginal method of snaring game is illustrated by colonial artist G. F. Angas. The exact location of the painting is not known so it cannot be certain this was a Kaurna snare.

Native wicker snare in the swamp, G. F. Angas, 1844 (NLA 2892737)

Other paintings show what Witongga was like.

(Extract from) Where Reeds and Rushes Grow, James Ashton, 1899 (AGSA)

(Extract from) Sun Rising, Adelaide Hills, James Ashton, c1900, (Private collection)

The fertile soils and the water of Witongga were quickly recognised and utilised by the settlers. The resulting disappearance of traditional food resources for Kaurna meyunna lead them to turn to what was then available. The first female prisoner in the Adelaide Gaol was the Kaurna woman Wariato who was convicted of stealing potatoes from the property of Thomas Payne at the Reed Beds. She was sentenced to 14 days hard labour in March 1841. Kaurna meyunna also had to take advantage of unexpected events:

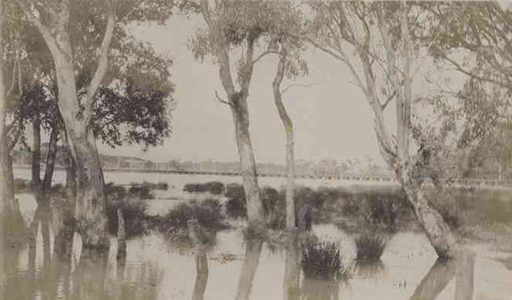

The Reed Beds are woefully flooded, and it is feared the damage to the orchards, gardens, vineyards, and growing crops in general, will be unprecedentedly severe. The natives were seen to be busy enough on Monday at different points of the river in collecting stray winter melons, and pumpkins, tobacco, palings, rails, and larger timber (South Australian Register Saturday 11 July 1846).

Floodwaters under the tramway viaduct, 1917 (SLSA: B 52985/13)

The dunal systems that fringed Witongga from Queenstown to Glenelg were Kaurna meyunna burial places, also called sleeping places. There are many stories, particularly in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, of the discovery of skeletal remains during farming, sand mining and building activity, or as erosion disturbed the dunes. Adelaide University geologist Walter Howchin noted that:

The banks of the lower reaches of the River Torrens, with the adjacent sandhills, must have been the chief camping grounds, as well as burial place, of the local tribe for generations. Many skeletons have been exposed at this spot by the erosive action of the wind, and in addition, the locality has proved to be the richest in the occurrence of stone implements that has come under the Author’s notice in South Australia (Howchin, 1934).

Mr J. Horsley has lived at Fulham Park for many years. He was there when Mr W. A. Blackler owned the property, and has seen many aboriginal skeletons taken from its paddocks. In commenting on the [recent] find Mr Horsley said that some years ago half of the sandhill from which they were taken was removed, and many similar skulls and bones found.

Mr Horsley said there was little doubt that parts of Fulham Park in days past had been used by the natives as a burial ground. During the time he was residing at the famous stud farm scores of skeletons were found. (The Mail, 1927:1)

In the old times Kaurna meyunna would see wilto eagle in the sky during the day and night. These appearances would announce the arrival of the seasonal cyclic movement (Winter/Autumn) from the cave and other shelters in the lower hills down to the plains and further to the coast. They travelled, usually following the rivers and creeks, using the knowledge and dingoes to smell where the freshwater springs, waterholes and other resources were along the way. They would re-trace the pathways to their ancestors, which were never far from water sources. At burial sites, they would not just simply place a flower, they would make fire and sleep in that place with them. Old burial places are still being found now.

The inundation of Witongga, whilst creating the fertile soils, caused problems as urban areas developed and in the early twentieth century Witongga was drained by cutting a channel to Wonggayerlo (Gulf St Vincent) as an outlet for the waters flowing down the river. The channel is called Breakout Creek. This brought to an end the ecological system of the river and the reed beds. Seventy-nine (or 60%) of the 130 plant taxa known to the area have become extinct since colonisation (Kraehenbuehl, 1996:180).

The Reedbeds must have presented a wondrous sight to early observers: there was probably a close resemblance then to some of the surviving coastal swamps in the lower part of the South East region of South Australia. Yet hardly any vestige of this vast area remains – surely an indictment of the activities of our forebears. Any chance to conserve the old Reedbeds has more than likely gone forever (Kraehenbuel, 1996:180).

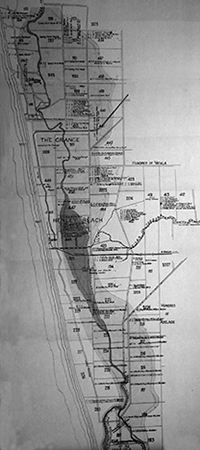

Extent of the river floodplain in the western suburbs, 1916 (Source, Smith & Twidale, 1989)

Ephemeral wetlands ‘View from 14th Tee West’, 1930 (Photo courtesy Grange Golf Club)

Capt. Charles Sturt was one of the early settlers in the Reedbeds, acquiring 390 acres of land in the northern portion and built his home, the Grange, there in 1840. The land included the upper reaches of the Port River (or Grange Creek) whose course once ran northwards through the area that is now West Lakes towards the sea. There have been many changes to the creeks and wetlands in that area. His home was located in:

… a very pleasant situation in a natural park of shady red gum trees … they would look across to the still largely tree-covered Adelaide Plain … The creek, which came winding southwards through the paddock, the upper reaches of the Pt. Adelaide River, ... and behind the house began the tea-tree and other flowering sandhill scrub which at that time was all that lay between them and the sands of an exceptionally wide beach … (Casson, 1972:7)

The Grange, E C Frome, c.1849 (Royal Commonwealth Society, London)

The Port River/Grange Creek near the Grange, n .d. (Barrow Collection, Flinders University)

An early painting depicts the upper reach of the Port River at Grange.

Bridge over Port River (Grange Creek), Beach Street, Grange, G A Reynolds (City of Charles Sturt)

Grange Creek (Port River) c1880 (SLSA PRG742_5_147)

In 1864 when Sturt was living in England his agents wrote to him that:

It is perhaps right to say that the natural advantages of the place are not what they were. The gums trees, for instance, are dying, as is the case in the thickly settled parts. We have never heard any satisfactory reason for their doing so, but it is the fact that even in the Parklands the gum trees wither and die. The tea tree also has to a great extent disappeared. (Casson, 1972:9)

The red sand dunes that bordered the eastern edge of Witongga are also nearly all gone.

There used to be, several kilometres inland from the coast, a belt of high red sandhills, vegetated with dense stands of native pines, eucalypts, sheoaks and acacia scrub. These older consolidated dunes – formed about 150,000 years ago - once stretched almost unbroken from Port Adelaide and the western side of Torrens Island to the Sturt River at Novar Gardens. There were extensive areas of these dunes in the area formerly known as the Pinery at Grange and at Royal Park, through the suburbs of Seaton, Findon, Fulham and Lockleys and in a long arc stretching from Netley through Plympton to Novar Gardens. Today you can see surviving remnants of these dunes, with some of their original vegetation still intact, in the Kooyonga, Royal Adelaide and Grange Golf Courses. If you are driving west down Grange Road, you drive over several prominent dune crests between Findon Rd and Tapley’s Hill Rd (Gara, 2008:1).

Red Dunes, Royal Adelaide Golf Club, Seaton

Thousands of tonnes of sand from these dunes were used to fill the extended wetland areas and grade areas in the construction of the Adelaide airport at West Beach. In the 1950s at the Pinery (Grange), sand companies removed the dunes stretching between Queenstown and the football stadium at West Lakes but there were still groves of native pines in between the sand dune swales and it was possible to ‘pick up the occasional native stone chippings’ (Kraehenbuel, 1996:180).

The Name Fulham

Colonial settler John White, who arrived in 1836, was one of the first settlers in Witongga. He named the land he purchased Fulham Farm, after the suburb in London where he was born. Fulham derives from the Anglo-Saxon fullen-hame ‘habitat of water fowls’ (Manning, 2010:295). It is not known if White knew the name was so apt for the land where he settled.