Mikawomma was a tree-studded open grassy plain between Yerta Bulti (Port River region) and Tandanya (location of Adelaide). Mikawomma was a place of hunting for paru meat and gathering mai vegetable foods.

Karl Winda Telfer tells of the hunting of kurka kangaroo rat during the season of bokarra and Wolta Bush Turkey.

The success of this hunting technique could only be achieved with the knowledge of fire. The hunters after finding the kurka’s warren would gather special tatta grass, which they would then bunch together to make the required number of ngurko tatta tufts of grass to be used in this hunting way. The hunters would go around to each hole and place mudlata small sticks in a criss-cross fashion about an elbows length down all the holes and stuff them with the tufts of grass except for the main entry. This was done to block any escape. They would then light a gadla parrandi kutyondi small fire, which was vital for the success of this hunting technique. One of the hunters would then light a tuft of grass from the fire and walk around setting the other grass alight while the other hunter manned the main entry. Kurka live underground in holes, like pingko bilby and marti bandicoot.

Once the grasses were lit, the hunter would use a wing of feathers from a certain bird to fan the smoke down the holes, when he would see a regular amount of smoke flowing out of the main entry he would then crawl towards the centre of the warren placing his yurre ear on the yerta ground so as to yurringgarnedi listen for the kurka gurlte kangaroo rat’s cough. Once he identified a spot where several coughs could be heard he would mark this as the centre chamber of the warren and would then begin to dig with a karko murra hand spade made from karko the she-oak. On breaking through the chamber many kurka would be gathered easily as they were still under the effects of smoke inhalation.

This smoking out technique was also used for obtaining pilta possum, warto wombat and other tree and ground borrowing animals. This one was all over this place Mikawomma and other places too. Sadly they are all gone today, I still got palti for those ones hunting songs, I would have loved to go hunting for kurka with the old people and cook them up over an open fire under the stars. Vedey goodey tuckers that one.

Wolta bush turkey was once a common site upon Mikawomma. The low alluvial grassy open woodland provided a perfect habitat for wolta, a ground dwelling bird. The season called Woltatti in the Kaurna seasonal calendar is the time when the mosaic cool burn-offs would begin. Wolta bush turkey and tatti climb links the bird’s pattern of behaviour to the star constellation Wolta as the constellation of the two stars can only be seen at this time of year. The traditional cultural bearers would have known when and where to be in that place at the right time by observing the sun rise at dawn, its arc during the day, its position at midday and its descent close to sunset. Then gazing the stars by night with a trained eye to identify and interpret the constellation of Wolta to inform the actions and movements of the hunters and the clans for the incoming season.

These keen observations would tell the people to burn off because that would bring wolta as the bird instinctively knows that there is always something to gain from fire either flushed out or caught by; same as the people. These stars also indicate the coming of summer rains which let you know that wolta was on the move, and that the hunter could use rain to his advantage, both sound and smell. This greatly increased his chances as he would be able to get closer undetected before spearing or netting a bird. If you were lucky enough to spear or net one then you had the tastiest itya paru flesh meat to eat that night.

Other hunting methods were also used, like using the kaya hunting spear, midla spear thrower and munta large game nets. Colonist Edward Stephens gave this description of using the kaya and midla spear thrower for hunting, as would have taken place in Mikawomma:

The spears were thrown by means of the wommera or meedla, as most natives called it. This was a flat piece of wood about two inches broad at the middle, tapering off towards each end in rapid curves with knots at the ends. In the upper knot, and pointing towards the hand, was inserted the tooth of a kangaroo, securely fastened with the sinews from the kangaroo’s tail. The other end was simply a knob to prevent the wommera from slipping through the hand when the act of projecting the spear was complete. The point of the tooth was pressed into a hole in the blunt end of the spear, the other end of the wommera was held by the third and fourth fingers of the right hand, resting on the palm of the hand and between the finger and thumbs. The first and second finger and thumb grasped the spear. The hand with the spear, being raised and drawn back – the distance almost instinctively judged – then the spear was thrown with all the force necessary, and being propelled by the wommera, which acted with the leverage of an additional and very long arm, the distance that could be covered was something enormous. These spears were but seldom, if ever, used in battle (Stephens, 1890: 485-85).

Early colonist and artist Frederick R. Nixon walked through Mikawomma in May 1838 from Yerta Bulti to Tandanya, just 18 months after colonisation. He described it this way:

Having taken the necessary bearings by compass for the town, we 'sloped' away through some sandhills covered with scrub, all attractive from their novelty; and getting on a track, left our legs to their duty, while our eyes were feasted with the scene before us. The Mount Lofty range in any age - whether in a state of nature or changed by the hand of man, will always be beautiful. But the plains, as we passed along, offered the most pleasing varieties in scenery. Clumps of trees in picturesque forms were scattered all around; the intervals being covered with the richest meadow. The course of the Torrens was easily distinguished by the continuous belt of luxurious foliage which bordered its banks.

Turkeys (or properly bustards) occasionally made their appearance in the distance; while close to us, other members of the feathered family, such as cockatoos, paroquets, and plovers darted by us in hundreds. All this, no doubt, was charming to our eyes, which had been so long confined to the eternal circle of sky and water. (Adelaide Magazine, 1st February, 1846)

Colonel Light also made some comment saying that Mikawomma was ‘a plain that has not a rock, tree or bush in the way for six miles’ and was ‘a flat where carriages of any description could run at once without the trouble of making a road!’ to get between the port and the town (Elder, 1974:99, 103).

(Extract from) View from the Leads of Prospect House, looking towards Hindmarsh, S. T. Gill, 1850 (AGSA Collection)

Narno Wirra, native pine forest (The Pinery)

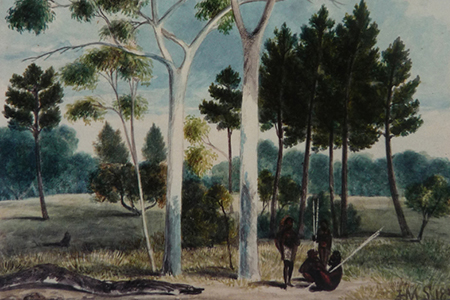

On the western edge of Mikawomma and south of Yerta Bulti (just south of the Old Port site) was a narno wirra, native pine forest, called The Pinery or the Pinery Estate by the settlers. The narno wirra stretched south along a very old sand dune to the east of the (Port) river/creek towards what is now called Grange. For Kaurna, narno wirra was a place where tarnda kangaroo, kuri emu and pundonya goanna could be hunted. Colonial artist John Skipper painted a group of Kaurna meyunna in one narno wirra. It cannot be certain if the forest depicted is The Pinery as there were other large forests of narno elsewhere on the Adelaide Plains.

(Extract from) Pine Forest, J. M. Skipper, 1838 (AGSA Collection)

There was also wodni Quandong, minno Golden Wattle, Sheoak, Banksia and Tea-tree there. Wodni provided good eating fruit.

Narno Native pine, Wodni Quandong & Minno, Golden Wattle, The Pinery, 1958 (Photo D. N. Kraehenbuehl)

Botanists Fenner and Cleland described the area in 1935:

The Pinery on the East Side of the Port River between Alberton and the Grange.

The Pinery consists of a sandy, slightly raised ridge, a consolidated sand dune, stretching several miles close to the eastern bank of the river. It has a very interesting flora and contains a few plants which are rare. It also shows affinities with the mallee scrub in having Grevillea ilicifolia var. ililifolia. At one time there was quite a forest of Native pines (Callitris propinqua [now preissii] with Peppermint gums (eucalyptus odorata [mis-identity for E. porosa] and some black tea-tree (Melaleuca pubescens [now M. lanceolata], Eucalyptus leucoxylon and Sheoaks (Casuarina stricta [Allocasuarina verticillata]. Much of the timber has been cut out, though a considerable number of pines still exist and young ones are coming up (Kraehenbuehl, 1996:189).

Narno Native Pine grove in the Pinery, Grange, 1955 (Photo D. N. Kraehenbuehl)

Narno Native Pine, 2012

Aboriginal Reserves on Mikawomma in the 19th Century

In the 1840s three Aboriginal Reserves were set aside on Mikawomma, in what are now the suburbs of Kilkenny and Renown Park in the City of Charles Sturt.

It was intended that the Aboriginal Reserves would be used by Aboriginal people for farming using European farming techniques. Aboriginal people were not agriculturalists and worked with the land in vastly different ways to Europeans. The idea that they would quickly become European-style farmers and agriculturalists was probably misguided and did not become a reality.

In the settlement of South Australia provision was made for the retention, or allocation, of land for Aboriginal people. South Australia’s founding document, the Letters Patent, signed by King William IV on 19 February, 1836 stipulated that:

… nothing in those our Letters Patent contained shall affect or be construed to affect the rights of any Aboriginal Natives of the said Province to the actual occupation or enjoyment in their own Persons or in the Persons of their Descendants of any Lands therein now actually occupied or enjoyed by such Natives.

These rights were never acted upon because the first South Australian Commissioners maintained that no such ‘actual’ possession or enjoyment could be demonstrated by Aboriginal people (as there were no buildings or farms as in the European tradition).

When the European land tenure system was introduced in South Australia, it divided Aboriginal lands into Counties, Hundreds and Sections. Over time sections were further divided into part sections and allotments. Portions of land settled were also to be set aside as Aboriginal Reserves. Under the administration of Governor Gawler (1838-1841), Matthew Moorhouse, Protector of Aborigines (1839-1856), was active in seeing that land was dedicated for Aboriginal use (although in the Adelaide district he had to ‘choose’ land that had not already been allocated to the first settlers before 1840). Thus prime Kaurna Meyunna tribal land along Karrawirraparri-Tarndaparri River Torrens was not available.

In 1840 Governor Gawler set aside at least twenty two sections, comprising 1610 acres (651 ha), for Aboriginal use or benefit. By the 1860s over 4700 acres (1900 ha) had been set aside in 42 reserves in 27 different Hundreds. These Reserves did not include specific Aboriginal mission stations such as Point McLeay-Raukkan (on Lake Alexandrina, established 1859) and Poonindie (near Port Lincoln, established 1850) or Piltawodli, the Aboriginal Location (in Adelaide, established in 1837).

In 1840 a correspondent in the South Australian observed after the dedication of the first few reserves that:

These reserves are not all occupied, neither are they likely to be for some time. We cannot expect to see a wandering race of people become fixed in their habits in the short space of time they have been in contact with Europeans (South Australian, 29 September 1840 p. 3).

By 1841 it was apparent that Kaurna Meyunna clans and other Aboriginal people were not becoming small farm holders. In 1842 the reserves were then offered for lease for a seven year period for agricultural purposes, with a loose intention that the income generated contribute to Aboriginal wellbeing. The income was mainly absorbed into general revenues. In 1848 Moorhouse outlined that:

These reserved sections were intended first to settle the natives upon them provided that any native can be induced to settle, and second provided they would not for some time to come, it was thought that a revenue might be produced by letting them and the proceeds were to be applied to the use of the natives.

In 1849 when the first leases expired there was no attempt to offer the land to Aboriginal peoples or to give them any control over the use of the land. The land was again let for private purposes, a pattern that continued until the land was resumed by the Crown for other purposes or subdivision in the 1880s. The dedication of Aboriginal Reserves did not provide any real benefit for the Kaurna Meyunna clans and other Aboriginal people and there are examples of Aboriginal people being hindered by authorities and others in their attempts to take up the land.

A few reserves were allocated to Aboriginal people outside of the district of Adelaide, to Aboriginal women who had married white men. The first was to the Kaurna tribal woman Kudnarto who married Thomas Adams in January 1848, the first Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal marriage in South Australia. In May 1848 she was allocated 81 acres on Skillogolee Creek, near Auburn (Section 346, Hundred of Upper Wakefield). After her premature death in February 1885 her husband was not permitted to retain the land for the benefit of their two young children, although use of the land by her family and descendants in perpetuity had been an intent of the land allocation. Her son, Tom Adams junior, later tried, unsuccessfully, to have the land returned to them. Their mother is most likely buried on that land. Kudnarto is an apical ancestor for many Kaurna descendants in Adelaide today (for further information about Kudnarto see Kudnarto http://kudnarto.tripod.com/).

The Aboriginal Reserves in the City of Charles Sturt

The City of Charles Sturt is in the County of Adelaide and lies mostly in the Hundred of Yatala. Portions of the northern and southern coastal areas of Council are in the Hundreds of Port Adelaide and Adelaide respectively.

The Hundred of Yatala stretches from the foothills east of Tea Tree Gully, to the western sea, Wongga Yerlo and lies mainly between the Little Para River and Gould Creek to the north and Karrawirraparri- Tarndaparri River Torrens to the south. There were five Aboriginal Reserves set aside in the Hundred totalling 358 acres (approx. 145 ha): Section 411, 80 acres; Section 2067, 71 acres; Section 2069, 43 acres; Section 2174, 78 acres; and Section 2175, 86 acres. Sections 2174 and 2175 were in the eastern side of the Hundred and located on the northern bank of the Little Para River, straddling what is now One Tree Hill Road, Golden Grove/Gould Creek, in the City of Tea Tree Gully.

Sections 411, 2067 and 2069, totalling 194 acres (78.5ha) were in the area that is now the City of Charles Sturt. The Surveyor-General’s map of the Hundred of Yatala in the 1860s (below) shows the Reserves. Sections 411 and 2069 were side-by-side, straddling the Torrens and Regency Roads intersection, Kilkenny. Section 2067 straddles the Torrens and South Roads intersection, Renown Park. In the 1860s South Road did not continue north of Torrens Road. A contemporary map (below) shows the area of the Reserves.

Hundred of Yatala (Western region), Aboriginal Reserves 1860s

These Reserves were never allocated to Kaurna or other Aboriginal peoples. In 1842 Sections 411 and 2067 were leased for seven years to a Mr William Bay and Section 2069 was leased to a Mr Lewis Hanson. There followed a series of leases and leaseholders until the land was resumed for other purposes in the 1880s. From 1885 the Aboriginal Reserves were able to be resumed by the Crown for other purposes or subdivision under the provisions of the Crown Lands Amendment Act. Many were subdivided and reallocated as workingmen’s blocks to provide land for low income earners or the unemployed. By then the land in the vicinity of Adelaide had potential as urban allotments rather than agricultural land.

Section 411

Section 411 is bounded (approximately) by what is now Torrens & Regency Roads (south), Hassell Street (east), First Avenue (north) and Hanson Road (west), Kilkenny. The area is now mainly used for commercial and light industrial purposes and includes the Arndale Central shopping centre and the Greater Union cinema complex.

Arndale Central Shopping Centre

Section 2069

Section 2069 is bounded (approximately) by what is now Torrens Road (south), Regency Road (west and north) and Goodall Ave (east), Kilkenny. The Section was subdivided in the late 1880s and in the 1890s was known as Yatala Blocks. In July 1927 the Woodville District Council changed the district name from Yatala Blocks to Challa Gardens. Challa is said to be an Aboriginal word (language group unknown) meaning ‘good soil’. The former reserve now includes the Challa Gardens Primary School, private housing and commercial premises. The school was established in 1926 as the Kilkenny North Public School with the name changing in June 1928 in line with the district name change.

Challa Gardens Primary School

Section 2067

Section 2067 is bounded (approximately) by what is now Torrens Road (south), Days Road (west), Lamont Street (north) and Harrison Road (east), Renown Park. From 1876 it was held by a Mr Thomas Cowan paying a rental of 60 pounds per annum under Aboriginal Lease 77. Cowan was a large landowner and in the 1880s held 12,000 acres (4,850 ha) of freehold and leasehold land within 50 miles (80 kilometres) of Adelaide in the Hundreds of Port Adelaide, Yatala, Grace, Bremer, Alexandrina, Goolwa and Willunga. He was also a Member of Parliament for the electorate of Yatala for one term, 1875-1878. He offered all his landholdings for sale by auction in November 1883 but the lease was not sold as in November 1885 he offered the crop growing on Section 2067 for sale. He had encountered business difficulties in the 1880s and a meeting of creditors was held in March 1885 and he was listed in Insolvency Court hearings in November 1887. In April 1886 the lease was cancelled and the area then subdivided for workingmen’s blocks. The area is now mainly suburban housing.

South and Torrens Road Intersection

Workingmen’s Blocks

On 16 July 1889, the Premier, Dr Cockburn, stated in the House of Assembly of the Homestead (Workingmen’s) Blocks scheme:

Having attracted our population in this way the question is how to fix the population on the soil. One of the best ways of fixing the population is that scheme now in existence with such good results known as the Homestead Blocks. We consider that scheme is full of advantages. We believe it is to the interest of the country to give every man as far as possible a share in the soil. It fosters a spirit of independence, and when brought into operation will solve for ever the question or the unemployed. The reports on the Homestead Blocks are exceedingly favourable. One of the last reports shows that 867 block holders are doing fairly well, and that only nineteen out of those have any intention of abandoning their holdings. We shall take every step to settle block holders on any land the State has available for that purpose.

The next day in the Legislative Council the Government stated that:

The Government is impressed with the necessity of extending the homestead block system, and with that view we shall cut up nearly the whole of the aboriginal reserves and the useless police paddocks which are near centres of population. The Government has spent two and a half millions on immigration, and it is deemed very right that we should give the poorer classes an interest in the soil.

The ‘poorer classes’ did not include the tribal clans of Kaurna Meyunna.

Further Reading

Berg, Shaun (ed) (2010) Coming to Terms: Aboriginal Title in South Australia, Wakefield Press, Kent Town.

Ellis, Julie-Ann (1995) Public Lands and the Public Mind: Origins of Public Land Policy in South Australia 1834-1929 Doctoral Thesis, Flinders University.