There is considerable traditional knowledge held by Kaurna cultural custodians and other Aboriginal cultural custodians, non-Aboriginal scholars and in paintings, books, journals and reports which detail Kaurna cultural practices and life structure. This knowledge is too broad and detailed to include it all so only some aspects of cultural practices are mentioned in these Kaurna web pages. Three overarching practices are introduced below.

Gadla Warra Fire Talk: Land Management and ‘Firestick Farming’

Kaurna have sustainably managed the natural resources of their environment through cultural practices for untold generations. Harvesting of vulnerable plants and animals was carried out according to seasons to ensure that animals, plants and people could live in a harmonious balance.

Kaurna meyunna managed the land and animals for thousands of years through the planned and judicious use of fire. Gadla burtulto purunna ‘fire stick farming’ combined the knowledge of the seasonal systems and the ecological and biological knowledge; the seasonal winds, animal’s life cycles, how the grasses and other plants grew. The deep knowledge of the rivers and creek beds and the water levels they contained at the seasonal times of burn off were also very important as they created pathways of refuge for many animals, as the fires would often burn towards the river valley’s edge.

At the right times old grass and other vegetation was burnt, enabling lush new growth to flourish to attract game for hunting. This thinned the vegetation in some areas to provide a more open landscape, suitable for animals to graze. In other places it was left thick to provide cover and concealment for hunters. Many indigenous plants also require fire for their seed to germinate and are well adapted to proper fire regimes.

Gammage comprehensively outlines Aboriginal land management practices throughout Australia in his book The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia (2011) and in the Adelaide region in the chapter The Adelaide District in 1836 in the book Turning Points: Chapters in South Australian History (2012). Gammage documents the many early writings which reference the temperate lands as having the appearance of a ‘gentleman’s park’, with open grassed woodlands and areas of forest eminently suited for the colonisers’ agricultural purposes.

As regards the general appearance of the wooded portion of this province, I would remark, that excepting on the tops of the ranges where the stringy bark grows; in the pine forests, and where there are belts of scrub on barren or sandy ground, its character is that of open forest without the slightest undergrowth save grass … In many places the trees are so sparingly, and I had almost said judiciously distributed as to resemble the park lands attached to a gentlemen residence in England (Sturt, 1849 in Gammage, 2011:7).

And South Australia’s second Governor, George Gawler declared that landscape was ‘just like a nobleman’s park nicely wooded’ (Cathcard, 2009:77).

An early colonist, William Finlayson, described what he saw when still on the ship as he travelled along Wonggayerlo (Gulf Saint Vincent) in 1837:

… before next day's sun arose a great change had taken place in the landscape before us. The watchers on deck, for many did not go to bed that night, beheld a fire on one of the hills which seemed to spread from hill to hill with an amazing speed. What is the meaning of this, every one asked but no one could answer. All on board were now awake and on deck looking at this grand yet, to us, who knew not of its cause, fearful conflagration. Since then I have seen many fires of the like kind but never one so grand and extensive as this, it seemed as if the whole land was a mass of flame. Still the question was unanswered what is the cause, what is the meaning of this. Knowing ones shook their heads and said I believe, it is a signal like the beacons of old to the tribes beyond the hills to gather, they have seen our ship and will come to destroy us, - others would say as they gazed at the grand sight before us - don't you see that savage throwing wood on the flames and some persuaded themselves that they could see - at the distance of 15 miles the form of a man. We sat long watching this grand and mysterious sight, - then toward morning, having committed ourselves to our heavenly Father's care retired again to rest. In the morning what a change had taken place, the whole range as black as midnight - except where trees were burning. The white dry grass was all gone, and shortly after we landed the mystery was explained - at the end of summer as this was, the natives set fire to the long dry grass to enable them to obtain more easily the animals and vermin on which a great part of their living depends.

Kaurna Palti Meyunna: Dance, Song and Ceremony

Providing for basic needs through land management, fishing, hunting, food collection and so on would occupy only several hours a day. The rest of the time was available for telling story and teaching the young about the natural lore and the law of the land. Gammage says of the relationship between Aboriginal land management and cultural practices, ‘[i]t made life comfortable. Like landowning gentry, people generally had plenty to eat, few hours of work a day, and much time for religion and recreation’ (2011:4).

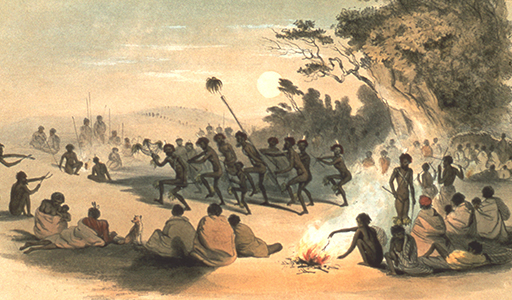

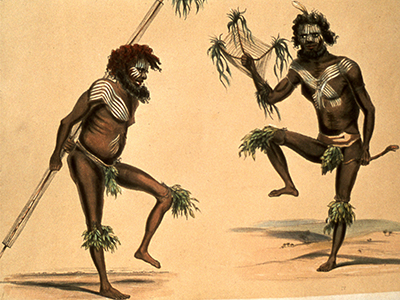

Culture and dance were a part of the natural cycles, many of the palti songs/dances were held during nights when kakirramunto the full moon would rise above Yurridla the two ears, the peaks now known as Mt Lofty and Mt Bonython. Each of the Kaurna clans had their own version of palti. Many of the ceremonial gatherings were witnessed by the early settlers, after the founding of the town of Adelaide in 1837 and onwards. One dance ceremony, the Kuri, was painted in the 1840s. This and other Kaurna cultural ceremonies continue to this day.

The Kuri Dance, 1847, G. F. Angas (South Australia Illustrated)

Kuri Palti, Paitya, sand dunes, Wonggayerlo, 2007

Kuri Palti, Paitya, sand dunes, Wonggayerlo, 2007

Leaders of the Kuri Dance G. F. Angas (AGSA Collection)

Kuri Palti, Paitya, sand dunes, Wonggayerlo, 2007

The Kuri palti was vividly described in the newspaper in the 1840s, Native Corroborees - South Australian Register, June 1844.

Burial Practices and Places

Laying people to rest and respecting their sleeping places was an important part of culture. Many of these sites were yawandi yerta camp places where the tribal relatives would come back to visit and pay respect to their dead. These places are still important to this day, even though they are covered over by our urban areas. Many of the burial sites in Adelaide and across the plains are still there and the sleeping ancestors are still being uncovered.

Fresh kauwe water was never far away from these places, a spring, creek or river. One such place is in a suburb which is today called Rosewater. There was a camp place/sleeping place there in amongst low laying sand hills close to a fresh water spring. This spring was a source of fresh water for Kaurna meyunna for thousands of years. They would stop there and use it each season on their journey towards and along the coastline.

During the sprawl of settlement and the loss of tribal lands (which cut off the tribal patterns and cultural associations), the settlers of the area began to utilise this source of kundonye kauwe sweet water. And because this water was so sweet the settlers named the place rose water. That’s how the suburb received its name, from the kauwe water of an Aboriginal spring. One of the sad things which occurred there was that in the later years of the 19th century it was turned into a dump and, once full, it was burned and amongst the debris was ancient ancestral remains.

There were many important burial places in the area now occupied by the City of Charles Sturt. Aboriginal ancestral remains continue to be discovered, particularly in the old dunal systems or along the river. The potential to uncover burial sites during development is an issue to be aware of. Any Aboriginal sites located are dealt with under the provisions of the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1988. In parallel with archaeological activities, Kaurna meyunna have become more active in leading the repatriation and cultural practices for ceremonial reburial which reflect traditional customs.